OOJ #4

Desire-driven triptych starting in the mid-20th century and ending with the Apple Vision Pro:

The 1950s/60s mutation of capitalism’s technostructure into the manufacture of desire & the market for attention.

The 1980s/90s emergence of computers, the endless complexification of financial products and televisual media mirroring this effect.

The 00s/10s full-scale hypermodulation facilitated by the rise of platforms and content creators as politics atrophies.

Let’s go.

Pay Attention, Attention Pays

Much of this first section is lifted directly from Yanis Varoufakis’ Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism (TF), which I’ve been reading in recent weeks.

His explanation of the dual nature of labour is fascinating, delivered in the most accessible style I’ve ever encountered.

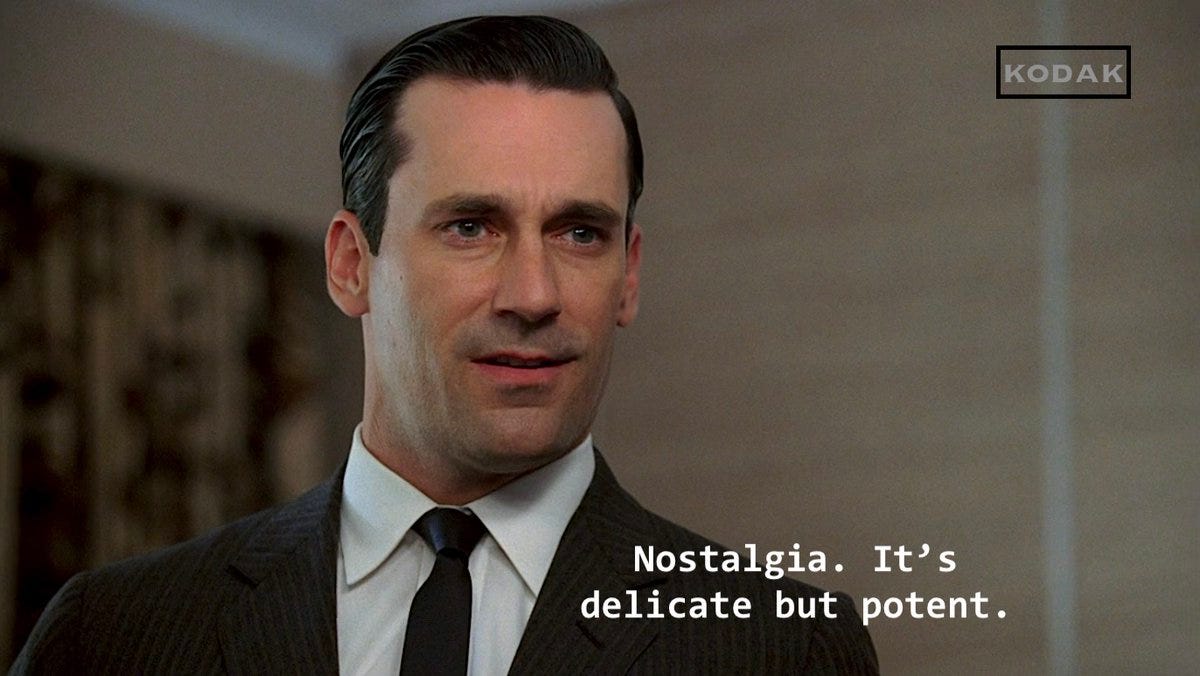

As is the discussion of capitalism’s mutation into so-called ‘late capitalism’ in the advertising offices of Manhattan, a phenomenon embodied by Don Draper.

Varoufakis points out that capitalism has become the only show in town thanks to its ability to continuously find new territory to capitalise…

“Assimilating wherever possible any experiential value it encounters into its exchange value chain.” (TF, p. 32)

However, it reached something of a crisis point in the mid-20th century; with every inch of the world’s surface already capitalised (or deemed out of bounds by the USSR) and the cosmos still just out of reach…

Capital turns inwards:

“Each time the onslaught of exchange value has overcome its defences, experiential value has gone underground into the catacombs of our psyche. It is there that Don Draper […] discovered it, retrieved it and, yes, commodified it.” (TF, pp. 32-33)

As summarised more pithily in Draper’s self-proffered marketing philosophy:

“You are the product. You, feeling something.” (Mad Men, S02, E01)

Or James Poniewozik’s version of the same thought:

“You don’t buy a Hershey bar for a couple of ounces of chocolate. You buy it to recapture the feeling of being loved that you knew when your dad bought you one for mowing the lawn.” (Time)

Essentially, Draper embodies the essence of capitalism’s post-war transformation:

“The discovery of a new market, namely the market for our attention.” (TF, p. 33)

TVs & Watching-Machines

While TV and radio provided an unprecedented opportunity to engage audiences, advertisers initially struggled to monetise an experiential phenomenon. As Varoufakis says, a TV show is “closer to a sunset than a tin of beans.”

That is until Draper’s insights became common understanding:

“…that the programme was not the commodity: it was the attention of the people watching it.” (TF, p. 39)

Chop the programmes into segments and sell short breaks in between; in an instant, a show goes from being ‘worthless’ to the perfect vehicle for instilling capitalist desire in the unsuspecting public.

This births up a whole new professional class overnight, a new group of experts:

“Alongside the scientists, analysts and professional managers, there were now creative types like Draper, as well as a whole raft of strategists and engineers working on new ways to manipulate and commodify our attention.” (TF, p. 39)

For a brief historical moment, this provides Draper-types with bottomless buckets of cash at the expense of a newly brainwashed American public.

But before long, advertisers encounter the very same problem that TV ads initially set out to solve…

When you only have a couple of channels to play with, advertising space is limited; capital runs out of the requisite territory to grow into. If capital can’t grow, it faces an existential crisis:

“Capitalism must commodify everything it touches [but] serious profits depend on failing to do so fully. If it is to avoid the fate of a school of predators that devours its prey so efficiently that it starves to death, capitalism relies on there being an endless supply of experiential values for its exchange values to trounce and cannibalise.” (TF, p. 34)

And so the obvious move is… more channels, more advertising space.

If more channels meant more shows — and potentially more interesting, meaningful cultural output — then this wouldn’t be a terrible thing per se.

But this isn’t the outcome. In the same way that the 1980s saw the computer become a crucible for the needless complexification of financial products…

“Back in the 1980s I remember a famous economist [Robert Solow] saying sarcastically that everywhere he looked he ‘saw’ the productivity gains brought on by computers – ‘everywhere’, he continued, ‘except in the productivity statistics.’” (TF, p. 54)

The same simulation of productivity occurs in television, as described by an industry insider commenting on a k-punk blog:

“TV companies are constantly jittery, fiddling and fussing with schedules to improve the ratings (and therefore retain/increase advertising revenue) while mostly just shifting the same old effluent around the schedules, or exchanging it amongst themselves (‘You’ve seen every episode of Friends over a hundred times – but have you seen it on our channel?’)” (Source)

The modulation of the content becomes a profit driver that obfuscates the lack of new content being created.

Rather than the ads being an add-on to the program, the program becomes the add-on to the ad.

“May not an ass know when the cart draws the horse?”

Hypermodulation Station

One of capitalism’s biggest flaws — exploitation, corruption, oppression aside — is that it always seems to assume the lowest possible levels of intelligence in its unwitting ‘consumer’.

It fails to anticipate people seeing through its tactics, becoming bored and frustrated with the same old content, the same old ads. Draper actually points this out himself later in the show:

“We are flawed because we want so much more. We are ruined because we get these things and wish for what we had.” (Mad Men, S04, E08)

And Vaourfakis sums it up neatly:

“It is one thing for our dreams to go unfulfilled. It is quite another to sense that our unfulfilled dreams, our frustrated desires, have been manufactured by others. The more our mass-produced cravings are satisfied, the less satiated we feel.” (TF, p. 50)

This produces an opportunity and a problem for capitalists.

The opportunity: the void available for filling with manufactured desires grows only larger; this gives capital its essential room to grow.

The problem: consumers become savvy to the centralised, salaried creatives that are producing their desires; as a result, they resent and abandon the medium.

This is where so-called cloud capitalists and their marketing gurus make the most underhand move of all….

Enter: the content creator.

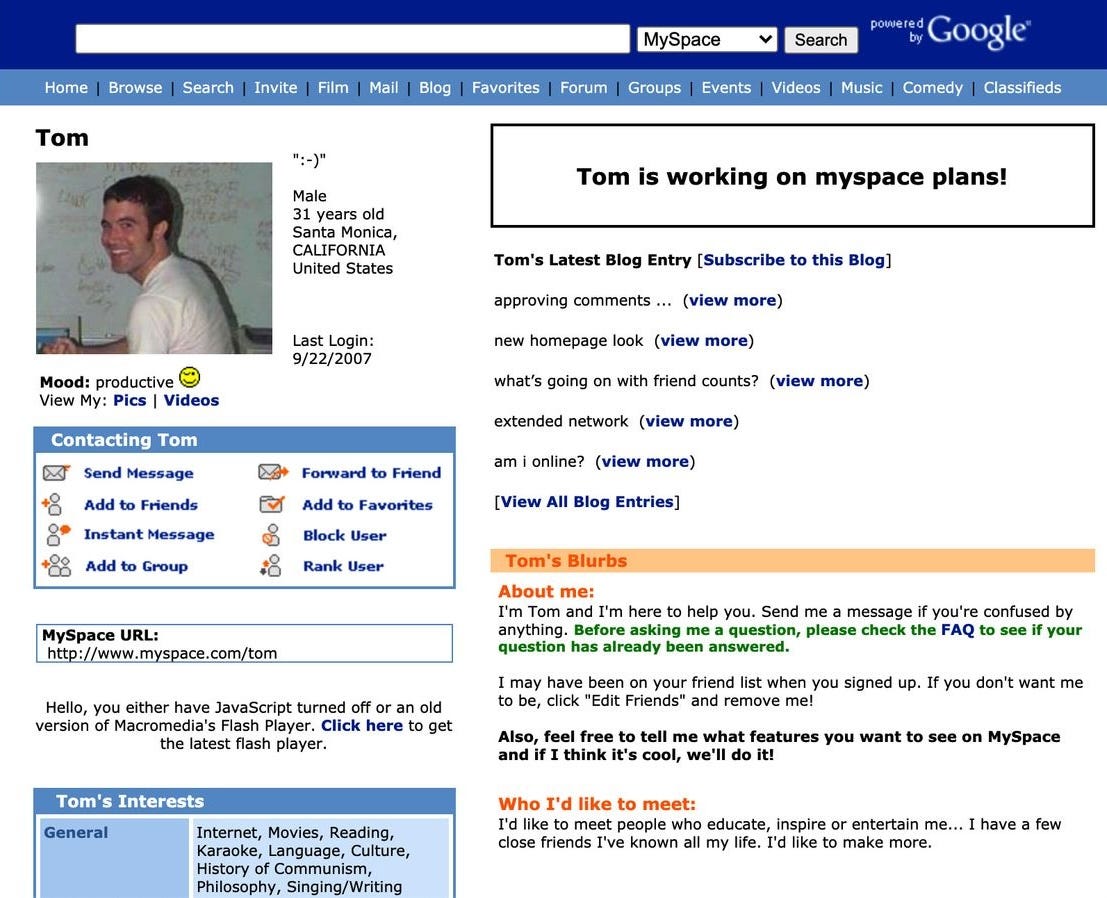

In the early days of social media, many wondered if these platforms represented a panacea. A genuinely social media, populated by ‘the people’, generating media for ‘the people’.

Naturally, advertisers couldn't let a good opportunity go to waste, and so they replaced ‘the creative’ with ‘the content creator’.

Now, our desires are manufactured by the same big businesses but sold back to us by content creators just like us; the manufactured nature of the desire is obfuscated by the peer-to-peer facade of the sales medium.

Even worse: not only do the content creators minorly modulate the way these desires are packaged, giving the impression that they’re eternally-new and always-authentic…

But the content produced is then minorly re-modulated, optimised for distribution across all platforms…

Creating an ecosystem of content that is different enough to hold your attention but similar enough to rot your brain.

I turn to Dominic Pettman’s excellent and underread Infinite Distraction (ID):

“Hypermodulation [is] the attempt to distract us from the fact that we are being synchronized to an unprecedented degree.” (ID)

‘Synchronisation’ is the mass homogenising of political will; while politics may be increasingly polarised, each pole is more uniform and uninspired than ever.

Not only do the content creators furtively instil you with the desire to buy their Partnered Product of choice, they generate a loop of infinite distraction that makes political action nigh on impossible…

“Break[ing] habits of thinking, being, and acting, which themselves have worked in tandem to foreclose new opportunities.” (ID)

The emergence of the Apple Vision Pro — and ‘VR’ writ large — is the next dystopic step in this process.

Not only is the same content endlessly modulated across platforms but a personalised feed of that content is distributed via a technology that collapses the plane on which political action used to take place…

And will eventually nullify the need to interact with that bricks-and-mortar reality at all. The much-memed notion of “locking in” actually serves to “lock in” one (terrible) political reality.

Reverse-Sync

I never want OOJ to become a forum for negative criticism only; we try to proffer solutions, even if said solutions are far bigger than this blog alone…

I don’t believe in the notion of unplugging. As discussed back in OOJ #1, the master’s tools will have to be used to destroy the master’s house, at least in part.

Pettman explains:

“As seductive as the notion of unplugging is, along with calls for a ‘slow thought’ movement, such notions can only function as the Romantic shadow to the cynical hijacking of technics by those deeply invested in what Steven Shaviro calls ‘plundernomics’.” (ID)

I’m more inclined towards re-synchronisation. The same technologies used to lull us into inaction could be the same technologies that awaken us from our stupor, instead inspiring a class consciousness for the cloud.

Pettman again:

“Synchronization is [only] an issue when it means the capacity to think, act, and be otherwise atrophies. But synchronization is to be welcomed, and produced, when it works against what Giroux calls ‘the disimagination machine’.” (ID)

That is, when it can be deployed against the “channelling of focus away from injustice, inequality, corruption, and exploitation.”

But how do we do this?

Especially in our situation where the platforms are so pervasive that there seem to be no legitimate means for communicating and coalescing outside of them…

A cloud for the commons is one idea: “creating software held in common and in the commons […] along with a host of site- or event-specific interventions or subventions”.

Pettman ends with a clever gag about the (then brand new) Apple Watch:

“The challenge is all the greater, however, to synchronize our watches now that we tell time by smartphone, or by Apple’s latest timepiece.” (ID)

Now the same question must be asked in light of new technologies:

How can we expand the Overton Window through which we look, the political horizons onto which we gaze, through a $3,500 pair of Apple-tinted glasses?