OOJ #11:

This is an abridged version of my BA dissertation: The Problem of Language in the Feature Films of David Lynch. It is a long read and I expect very few of you to read it in full, but it needed archiving for posterity so… let’s go.

Part 1: Talking — It’s Real Dangerous

‘The thing that language never is, never can be, but to which language is always moving.’ — Steve McCaffery

Since the very beginning of his filmmaking career, David Lynch has exhibited a fundamental distrust of, and reluctance to engage with, language.

Dennis Lim explains in his 2015 book David Lynch: The Man from Another Place that Lynch has always resisted the demands of press and critics alike to put the meanings, motivations, and processes of his films into words, pointing to this classic clip as evidence:

Lynch has suffered a fraught relationship with language for far longer than he’s been a filmmaker; Lim cites Lynch’s ‘“pre-verbal” years, a phase that lasted well into his early twenties.

This is a habit that has continued throughout his career; even his largest productions were marketed using ‘the most minimal one liners’; Mulholland Drive’s poster labels it ‘a love story in the city of dreams’, and Inland Empire is supposedly nothing more than the story of ‘a woman in trouble’.

Lynch did describe to Lim how he believes it inhibits the filmmaking process:

‘As soon as you put things in words, no one ever sees the film the same way […] and that’s what I hate, you know. Talking – it’s real dangerous’

But why does Lynch feel so strongly about language, why does he deploy it in such a self-consciously strange and enigmatic way in his movies?

Psychocriticism

Following a precedent set by critics like Todd McGowan and Slavoj Zizek, this essay examines Lynch’s films from a psychoanalytical point of view.

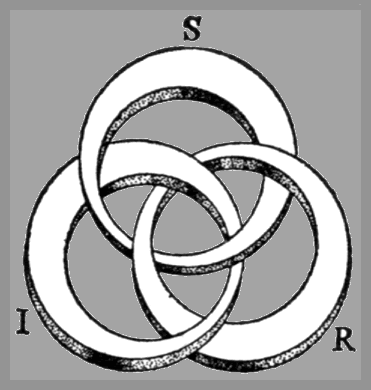

Take Lacan’s topological model of the psyche — the Borromean Knot. It consists of three closely related ‘orders’ — the Symbolic, the Imaginary, and the Real.

All three of these orders are interlinked, holding each other and all of us in a delicate psychological balance; if any one part were to be removed or severed, the knot would fall apart, and all three orders would be set free in disconnection.

The first section of this essay focuses on the Symbolic order, because the Symbolic is ‘about language and narrative’, it is all that comprises the ‘social world of linguistic communication.’

The Symbolic, through language, is…

‘the pact which links […] subjects together in one action, human action [is] founded on the existence of the world of the symbol’.

Not only does Lynch present a knowingly weird idea of the Symbolic, but he attempts to negate, disrupt, and repurpose it.

The second order of importance will be the Real.

‘The Real is the impossible’ according to Lacan; all that the Symbolic and Imaginary orders — those which constitute conscious reality — cannot represent.

Mark Fisher summarises it most succinctly and usefully:

‘The Real is an unrepresentable X, a traumatic void that can only be glimpsed at in the fractures and inconsistencies in the field of apparent reality.’

What Fisher highlights so pithily here, and what will become central to the argument of this essay, is the ‘desubstantialised’ nature of the Real, its ‘negativity’.

Zizek explains that the Real is not…

‘An external thing that resists being caught in the symbolic network [but a] fissure in the Symbolic network itself’.

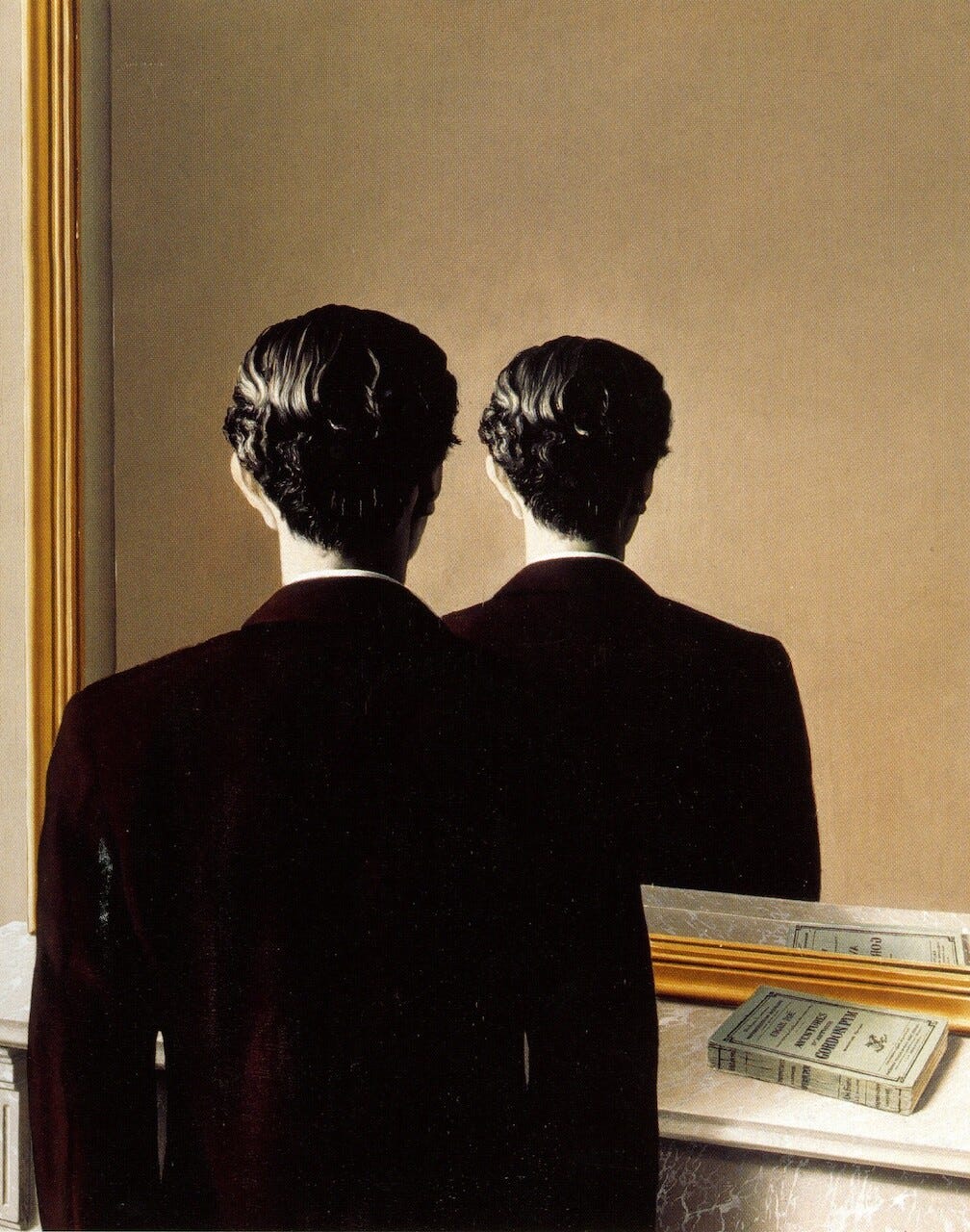

The third order, the Imaginary, is ‘the domain of images.’

It corresponds to the mirror stage of childhood development, wherein a child ‘misrecognises in its mirror image a stable, coherent whole self […] in order to compensate for its sense of lack or loss.’

Lynch identifies a crack present in the Symbolic order. Namely, that language, the Symbolic, is given an almost totalising power to define the self, and the self within the social field…

Even though it is, by nature, incapable of representing an essential and universal part of the human experience and psyche — all that exists within the Real.

An Anthem Of Conformity

Despite its fundamental inadequacy language is universally perceived as the utmost definitive authority.

1968’s The Alphabet, one of Lynch’s earliest short films, depicts the violent effects of an ‘intellectual discourse for rationalisation and structure’ through language.

The Alphabet depicts a child whose sleep is tormented by a relentless recitation of the alphabet that invades their previously peaceful dreams.

Grace Lee describes how the letters appear:

‘Secreted onto the screen through ruptured openings, [they] creep and spread like an infection before entering the head of the human figure, causing it to bleed and disintegrate.’

It is not just the letters themselves Lynch believes invoke the suffering; it is their ‘ceremonial delivery’, the ‘threatening chants like an anthem of conformity.’

Note also the booming adult voice that sings scales and arpeggios; far more enthused by the structuring elements of the words they sing, the organising form of language, rather than the words themselves or any meaning therein.

All this reflects Lynch’s concern with the ways in which language is dogmatically taught and codified; that the process of learning language is inherently violent.

The violence of the Symbolic comes through its rigid linguistic structures, locking unknowing individuals into social pacts that may keep society stable but depend on an outright denial of everything ‘Real’ in order to maintain that stability.

A Cry And A Name

Eraserhead is the perfect case study of this.

By introducing an entity that cannot be assimilated into the Symbolic through language, and thus cannot enter into the contracts upon which the social space is built, Lynch shows how essential the authority of the Symbolic to define individuals within social reality has become.

Critic Hedwig Schall describes how…

‘A man’s story begins with language, a cry and a name [and when] the newborn is immediately addressed and categorised in words as a boy or a girl […] these two moments of naming and castrating constitute the subject’.

A concern with naming can be seen throughout Eraserhead. The first line of dialogue that occurs is when Henry’s neighbour and later lover leans out of the apartment to ask ‘Are you Henry?’

Similarly, the first piece of text that the camera exposes is his name, ‘Henry Spencer’, stuck onto his mailbox.

By stark contrast, the baby in Eraserhead refuses to be differentiated.

When Mary, the reluctant mother, tells Henry that ‘[the hospital] still aren’t sure if it’s a baby’ at all, her choice of words is telling: the family are unable to differentiate the baby because they cannot define ‘it’ as male, female, or anything else.

What makes the baby so terrifying to its parents throughout Eraserhead is that it continues to cry, it constantly alerts them to its presence, its ‘being there’, but that it cannot be differentiated and so becomes a fissure through which the Real might be glimpsed.

It is this prolonged threat of the Real, brought about by language’s inability to differentiate the baby, that causes the film's climatic act of infanticide wherein Henry plugs the gap through which the Real could enter.

The result of this prolonged exposure to a ‘Real’ object is a pervasive silence in almost every other aspect of the film.

A pervasive silence inhabits the marital home – neither adult ever utters more than a few words to the other apart from the occasional outbursts of suppressed, confused rage.

The opening sequence of the film anticipates the child’s birth: absorbed in absolute silence, other than the ominous sound of wind that blows in the background, Henry’s head floats horizontally across the frame, he opens his mouth as if to scream but no sound escapes; he has become ‘arhetorical’.

England’s Most Unfortunate Sons

Lynch’s second feature The Elephant Man is similar to Eraserhead in that it presents a character who resists easy linguistic definition and assimilation into the Symbolic.

Unlike the baby in Eraserhead who is eventually destroyed for destabilising the Symbolic, John Merrick is able to socially interpellate himself and become assimilated into social reality thanks to his interactions with various texts.

After initially failing to impress the Hospital Administrator, Carr Gomm, with his awkward and mechanical repetition of biblical lines taught to him by Dr Frederick Treves, Car Gomm concludes that Merrick ‘doesn’t belong here’.

However, when Merrick is overheard reciting the 23rd Psalm — sections that Treves had not practised with him beforehand — Carr Gomm not only allows him to stay at the hospital but he is moved into a more comfortable set of rooms in the main wards.

On being visited by Mrs Kendall, one of London’s foremost actresses, who gifts him a copy of Shakespeare’s Complete Works, Merrick and Kendall recite a passage of Romeo and Juliet. When they finish Kendall says to him:

‘Oh Mr Merrick, you’re not an elephant-man at all, you’re Romeo’.

The text serves not only to transform Merrick from pariah into social subject, but furthers the interpellative effect by elevating him to the realm of so-called high art.

When the Governing Committee of the hospital convene to vote on whether Merrick should be permanently admitted to the hospital, the meeting is interrupted by a visit from ‘her royal highness Alexandrea’.

The princess reads a letter from Queen Victoria wherein Merrick, whom had been described immediately before the meeting by committee members as an ‘abomination of nature’, is interpellated for a final time and transformed into ‘one of England’s most unfortunate sons’.

A Hymn To Unreality

In 2001’s Mulholland Drive, a budding actress played by Naomi Watts is transformed from a naïf into a serious sexual subject.

Her character and her ‘flimsy comic-book moniker’ — Betty — are, according to George Toles:

‘So entrenched in naivete and the hokey paraphernalia of small-townness that her whole confected being is a hymn to unreality.’

However, when Betty attends an audition and begins reading her script a kind of ‘alchemy’ takes place, wherein she suddenly transforms into a character whose ‘hold on life and on her turbulent inner forces seems more fraught with consequence than our own.’

Through textual interaction, she is transformed from something alien and unreal into something ‘concrete’, something that ‘exists’, through language.

By having Betty enact a desire that is communicated and sustained through the language of the Symbolic via a script — a written text that belongs to the realm of the Imaginary — Lynch shows that language can reassert its own authority and distance subjects from the Real by acting as a mechanism for the reproduction of desire.

All these scenes represent Lynch’s identification of this problem, but they also provide the seeds of a possible solution:

If language is the foremost route away from the Real, then it must also represent a possible route back to it.

The motif of performance exhibited in these scenes — Merrick’s recitations and Betty’s audition — hints towards the key behind Lynch’s destabilising of the Symbolic:

Self-consciously uncanny language deployed in self-consciously performative spaces.

Part 2: Repeating, like an automaton

As seen in part 1, Lynch devotes a significant amount of the language in his films to highlighting the totalising power of the Symbolic and the way it perpetuates its authority by reproducing fantastical desires that inevitably fail before the Real.

However, he devotes a far greater proportion of his filmic work to attempting a redress of the fundamental imbalance he sees in the Symbolic’s hegemony.

The frequent reversion of many characters to linguistic cliché has been noted by critics as creating a depsychologising effect; his characters become internally flattened to the extent that they are nothing more than robotic devices for the hollow revival of historic movie tropes and genres.

However, if read another way, Lynch’s technique can be understood as having the opposite result: the repetition and doubling present in much of Lynch’s dialogue creates an uncanny effect that actually gestures back towards the underlying Real…

Full Blown Paranoia

Lynch’s frequent imitation of established cinematic genres has been read as symptomatic of ‘the failure of the future’ and a resultant ‘postmodern cultural scene’ which, as Frederic Jameson predicted, ‘would become dominated by pastiche and revivalism.’

However, Lynch’s case the use of cliche is somewhat more complex. Fred Pfiel argues that a postmodern text…

‘As in Cindy Sherman’s first acclaimed photographs [deploys cliché in order to] both to hybridise and hollow out those clichés’.

Jeffery, the protagonist of 1986’s Blue Velvet, has a conversation with Detective Williams that can be seen to ‘hollow out’ the clichés in which they speak. After finding the mysterious severed ear at the start of the film, Jeffery visits Detective Williams in his home in the hope of finding out whether the police have discovered anything about it.

‘I know you must be curious to know more’, Williams teases; Jeffery boyishly replies that he’s just ‘real curious’, Williams ‘was just the same way myself when I was your age’, it’s what ‘got me into this business’, an exciting business, Jeffery assumes, ‘but it’s horrible too’, replies Williams.

‘That’s just the way it has to be’, Williams concludes, before putting out his cigarette, swinging his legs off the desk, standing up wearing a pistol holster and loosened tie, with a police badge gleaming on his belt, and escorting Jeffery out.

‘Every phrase, is 100 per cent B-movie cliché [delivered] with all the wooden earnestness the actors can muster.’

In Blue Velvet’s closing scene Jeffery, Sandy, and Aunt Barbara spot a robin perching on a tree branch in their garden.

Despite all the perverse and traumatic events of the preceding days, the group have nothing more to say or conclude than ‘life’s so strange’ Their language is demonstrative of the fact they have become psychological ‘robots’.

Their cliched phrase, alongside the ‘bird’s obvious artificiality, the music’s cliched goopiness, and the hypercomposed flatness and stiffness of the mise en scene’ creates a sense that the characters have become so internally flattened because of an overpowered Symbolic order that keeps them distant from the Real; they have become depsychologised.

In Mulholland Drive: An old woman called Irene, who appears to have accompanied Betty on her journey to Los Angeles emerges arm in arm with Betty from the airport terminal.

Before parting, they speak to one another through strained smiles of glee in shameless Hollywood cliché, their words quite blatantly dubbed onto the moving image in post-production.

Betty, in all her naivety, ‘was so excited and nervous’ that ‘it was great to have you [Irene] to talk to’. Irene replies that she’ll ‘be watching for you on the big screen!’, ‘wont that be the day!’ Betty replies. They hug tightly, and eventually part ways with Irene departing in a limousine.

But Upon entering the car, Irene’s initial smiles of ‘self-satisfaction’ quickly turn ‘into demonic laughter, sadistic glee’...

As Richard Stein describes:

‘These are not real people, [but rather] affect-laden images in the psyche’.

All of this engenders a fundamental distrust between Lynch’s audience and his characters. It is no longer merely a concern that the audience might not have ‘gotten to the bottom of [them] yet’, but a ‘full blown paranoia that there may be no bottom here at all.’

A Fascination For The Outside

However, rather than simply representing the ways in which language has cut subjects off from the Real, Lynch’s use of cliché also has the capacity to invoke the Real…

To paraphrase Mark Fisher, Freud’s concept of the ‘unheimlich’ has been…

‘Inadequately translated into English as the uncanny; the word which better captures Freud’s sense of the term is the “unhomely.”’

Fisher’s choice of phrase draws attention to how the uncanny draws on ‘a fascination for the outside’, for that ‘which lies beyond standard perception, cognition and experience’, in other words: the Real.

Specifically, Fisher cites…

‘Repetition and doubling – themselves an uncanny pair which double and repeat each other – [that] seem to be at the heart of every uncanny phenomena that Freud identifies.’

Furthermore, Fisher suggests that the ‘eerie’, that which signals the uncanny, can be found ‘more readily in landscapes partially emptied of the human’,devoid of the psychological depth that would qualify them fully “human”, repeating cliches ad nauseam.

So let’s look at what Lynch's uncanny is really doing…

The second time that Frank mouths the words of Bobby Vinton’s ‘Blue Velvet’ in the eponymous film, he prepares Jeffery for a beating ‘by “kissing” lipstick onto his mouth and wiping it off with a piece of blue velvet’ as if Lynch is ‘daring to recognise the desire for each other that the two men’s newly discovered sadomasochistic bond induces them to feel.’

The men are doubled not only in their shared desire but in the repeated language of the song that has become the calling-card of the woman who represents the focal point of those desires; through the words of the song an uncanny effect is created.

This creates the sense that

‘What most of us consider to be our deepest and strongest desires are not our own, [they are] ‘copies of circulating, endless reproduced and reproducible desires’.

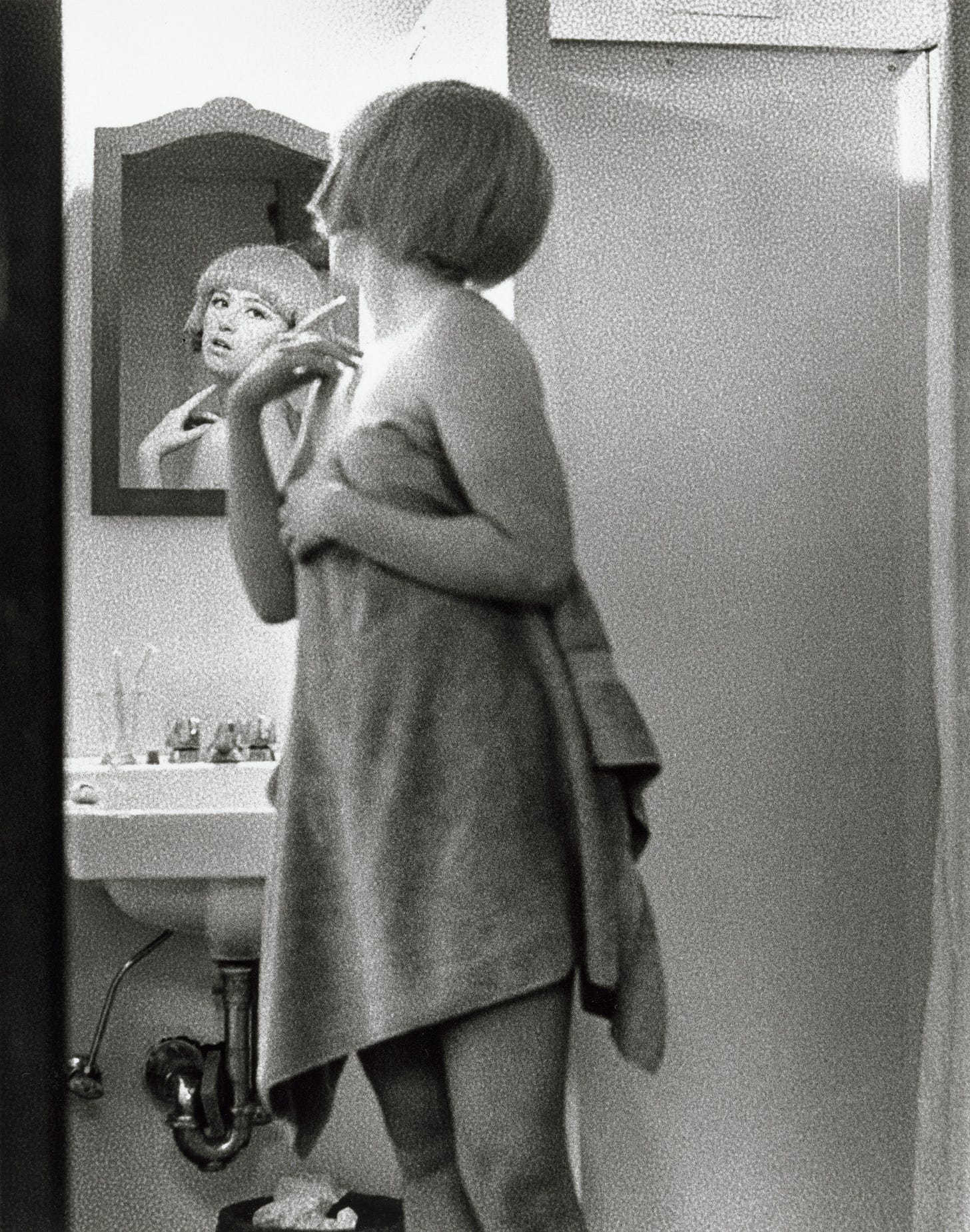

Lynch’s most recent feature Inland Empire formally manifests this effect. Laura Dern’s character Nikki Grace is herself doubled in the film.

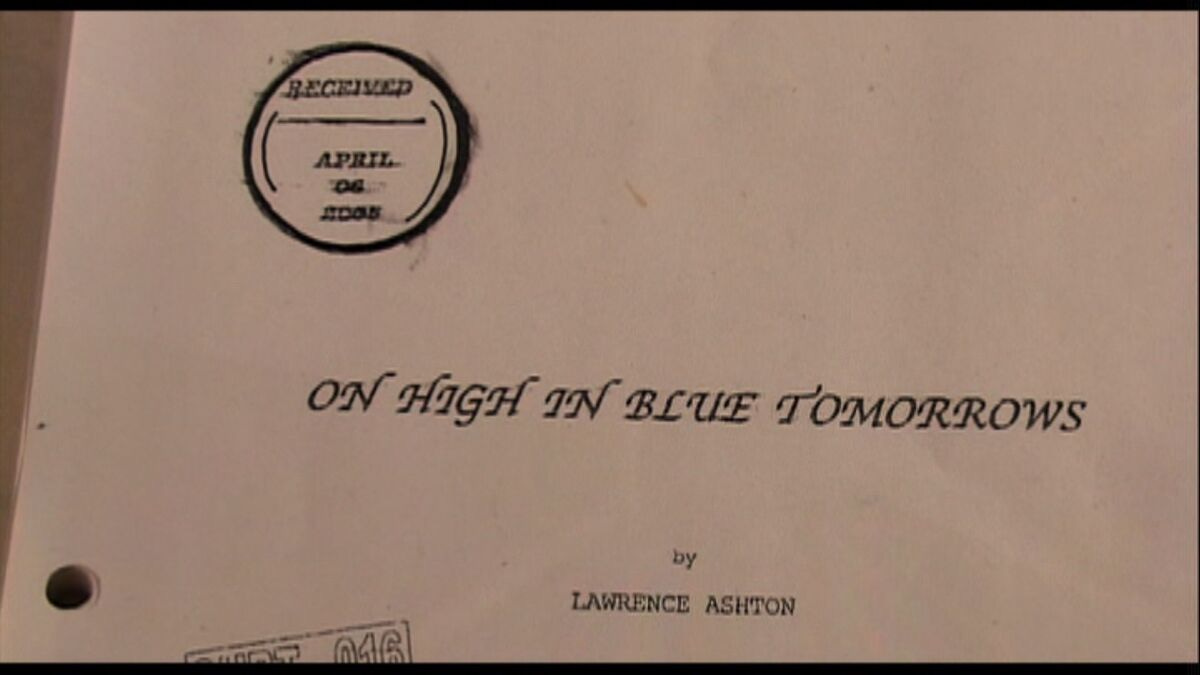

Grace, an actress, partakes in an initial reading of the script for an upcoming movie On High in Blue Tomorrows. However, the two presented realities — that of the shooting and production of On High in Blue Tomorrows and the filmic world of On High in Blue Tomorrows itself — quickly begin to blur and collapse.

Language is at the heart of this collapse: When an affair between Grace and her co-star slowly initiates in the ‘real’ world, it is predicated on filmic clichés such as the ‘tucked away little Italian restaurant’ that Grace cheekily demands her suitor take her to.

When Grace eventually becomes aware that the two realities are collapsing, saying to her co-star that ‘it sounds like dialogue in our script’, Lynch demonstrates that the desire she feels in the ‘real’ world for her co-star could just as easily be an uncanny repetition of the romance they portray on screen.

This effect is typified when Grace takes a turn through a door into a studio set where she sees herself reading the script of On High in Blue Tomorrows alongside her co-star and director; she is physically doubled.

In the same way that Frank and Jeffery’s doubled desire is reflected through the words of a hit record, Grace becomes acutely aware in this moment that her desires and fantasies could represent uncanny repetitions of the language in her script.

However, by simultaneously creating an uncanny effect through doubled and repetitious language Lynch is able to gesture back towards the Real that underlies the constructed Symbolic and thus begins to destabilise and undermine it.

Big Daddy

Zizek summarises this in his description of a ‘New Age preacher’: ‘the style of his words – the style of repeating, like an automaton’, rather than suggesting that there is ‘no bottom here at all’ as Pfiel posited, implies there lurks ‘beneath their kind and open stance […] some unspeakably monstrous dimension.’

Zizek goes on to describe how in Lynch’s films ‘the psychological unity of a person disintegrates’ into two realms:

‘On the one hand, a series of clichés, of uncannily ritualised behaviour’, the Symbolic, and ‘on the other hand, outbursts of the “raw”, brutal, desublimated Real’.

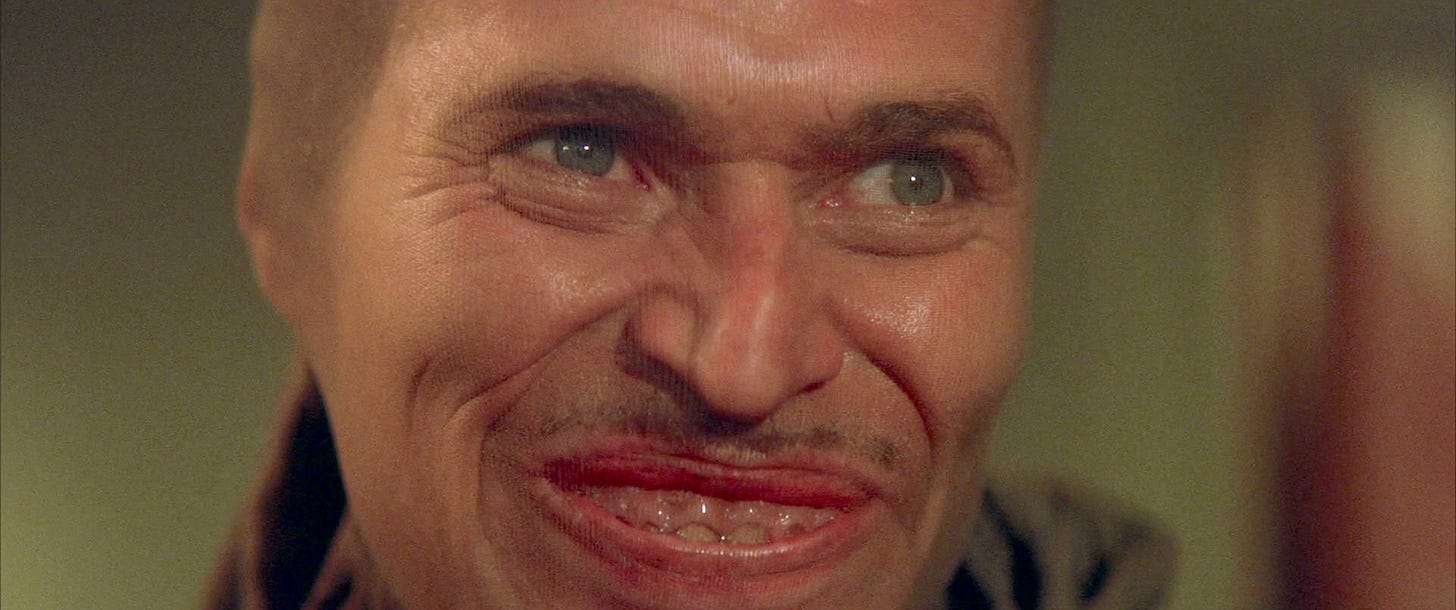

By contrasting the cliched but uncanny language of his more naïve characters with the ‘larger than life, hyperactive figures embodying pure enjoyment and excessive evil’, types that Zizek calls ‘pere jouissance (the father of enjoyment)’, such as Lost Highway’s Mr Eddy, Lynch makes it abundantly clear that the ritualised cliché of his naïfs proves that ‘our fantasies’, expressed through language, ‘support our sense of reality, and that this is in turn a defence against the Real.’

This juxtaposition is emphasised during a scene in Wild at Heart where Bobby Peru enters Lulu Fortune’s motel room to sexually proposition her during Sailor’s absence.

Lula, who predominantly speaks in Lynch’s more cliched language — the phrase ‘this whole world is wild at heart and weird on top’ from which the film takes its title is Lula’s line — is suddenly reduced to awkward, stuttering silence when confronted with Bobby, the pere jouissance.

After attempting to cover her body from Peru’s view, Peru grabs her by the neck and demands her to say ‘fuck me’. All Lula can offer by way of refusal is the ineffective repetition of ‘get out’, which she struggles to voice over Peru’s grip.

Peru, contrastingly, speaks in language that seeks to embody the Real; when Lulu tries to escape his grip, Peru screams:

‘Stop it! I’ll chew your fucking heart out girl!’

The sheer brutality and force of his words, as well as the unfettered urges they represent, are starkly opposed to Lula’s Symbolic banality which is shaken and exposed as fantasmatic façade by Peru’s announcement of the Real.

However, there is a conceptual flaw in Zizek’s argument. The Real, as both Fisher and Zizek himself have separately described, is a negative and desubstantialised entity; it cannot be positively represented.

So while Lynch goes some way to destabilising the Symbolic’s supremacy with language alone, it is when Lynch attacks the Symbolic and Imaginary realms simultaneously he can most forcefully destabilise conscious reality.

It is when Lynch deploys uncanny language in a destabilised Imaginary space, the performative space, that the Real can most readily be seen.

Part 3: Insisting On Fantasy To The End

By evoking and negating the third Order of the Borromean Knot, the Imaginary, in the form of self-consciously performative, and what I will later call ‘curtained’, spaces, whilst also using uncanny linguistic expression, Lynch foregrounds the fragility of the Symbolic-Imaginary reality and destabilises both orders simultaneously.

Mulholland Drive’s Club Silencio scene acts as a case study of how Lynch, foregrounding and negating the Imaginary and Symbolic simultaneously, is able to open up a gap in the fabric of knowable reality through which the Real can be most directly accessed.

This is evidenced in the way Betty, after glimpsing the Real during the events she witnesses at Club Silencio, disappears, and the oneiric reality that Diane Selwyn’s unconscious had constructed, the world that comprised the first half of Mulholland Drive, quickly begins to fall apart.

Lynch’s performative spaces relate to the realm of the Imaginary because the Imaginary encapsulates the ‘domain of images’, those images ‘with which we identify and which capture our attention.’

The Imaginary corresponds to the mirror stage of childhood development, wherein a child ‘misrecognises in its mirror image a stable, coherent, whole self’; such an image is ‘a fantasy, one that the child sets up in order to compensate for its sense of lack’.

As a result this fantasy image can be projected onto, ‘filled in by’, others that ‘we set up as a mirror for ourselves’, those that subjects may wish to emulate in their adult lives, such as parents, role models, or performers.

Free Zones

Lynch described Twin Peaks’ Red Room, in typically vague terms, as a space where ‘anything can happen […] a free zone’.

Richard Martin explores this further in The Architecture of David Lynch, saying that Lynch’s performative spaces are ‘free zones’ because they are isolated spaces and ‘isolated sequences within the larger frame of a film’, and as a result are spaces where ‘Lynch feels liberated to express concentrated bursts of emotion.’

Lynch believes that the ‘outside’ world grants too much authority to the Symbolic, to language that cannot represent the underlying Real; consequently, his performative spaces function as heterotopias because they invert the usually stabilising and structuring effects of the Symbolic by using language to create an unstable space of continuous emotional flux.

Sailor’s crooning performance of Elvis Presley’s ‘Love Me (Treat Me Like a Fool)’ at a club in Wild at Heart creates a fantasmatic scene that…

‘Moves from raw guitars to bubble-gum pop without a pause’.

When Sailor takes the microphone from the band onstage and begins to perform ‘the crowd accepts the radical changes in mood, allowing it to play host to seemingly incompatible emotions.’

This effect is typified by Eraserhead’s Radiator Lady, whose smiling face and ‘bubble-gum’ voice readily co-mingle, first, with her methodical crushing of the sperm-like creatures littering the stage with her high heel, and, second, with the violent decapitation of Henry whose head is replaced by that of his undifferentiated child.

Blue Velvet returns to this technique most frequently. Besides Dorothy Vallens’ performances at the ‘Slow Club’, the most overtly performative scene occurs when Ben, a drug dealer and pimp, draws a large set of curtains behind him and transforms the previously domestic space of the brothel’s reception room into a stage before beginning a suave performance of Roy Orbison’s ‘In Dreams’.

The performance is not only emotionally at odds with the perverse and malevolent motives for their visit, but also elicits vastly different emotional responses from his spectators: some in the brothel are moved to dance, some to stunned silence, and Frank to a twitching, seemingly irrepressible outburst of sexual rage: ‘I’ll fuck anything that moves!’ he screams after cutting off the tape halfway through the track.

Blue Velvet also manifests this effect in more subtle performative spaces. The mis en-scène of Dorothy’s apartment has been noted by critics to self-consciously resemble a stage or set, and thus represents a subtler but no less evocative and fluctuating performative space.

Jeffery is transformed from the gazer that voyeuristically peers at Dorothy through the door of the wardrobe in which he hides, to the gazed upon and the sexual submissive when Dorothy discovers him; she forces him to kneel and strip in front of her.

This effect is heightened further when Frank, another pere jouissance, enters the scene. Betsy Berry describes that ‘when Frank first enters the room, he quickly admonishes Dorothy’ for saying “Hello Frank”: “It’s Daddy, you shithead!” – Frank is initially the aggressor, the dominant.

However, in a doubling repetition of the flux that Jeffery experienced, ‘when the sexual act begins, it is Dorothy who is “mommy”’; Frank’s initial aggression moves swiftly to total child-like submission, and oscillates between these poles several times throughout their encounter.

Jennifer Hudson summarises this effect psychoanalytic terms; she suggests that these spaces undermine the totalising power of language and the Symbolic by facilitating a return to a discourse that exists beyond language.

Citing Mulholland Drive’s Club Silencio scene, she notes how in these spaces ‘language fails to define and construct reality and being within a Symbolic order’; Lynch instead creates a space that ‘uses emotional responses’, the fluctuating changes in mood that Foucault and Martin highlight, ‘as a fluid and sensual language that expresses what words cannot.’

Boundless Boundaries

Lynch’s performative spaces mark a return to a ‘semiotic chora’. Julia Kristeva’s concept of the chora describes the earliest stage of psychosexual development wherein the ‘pre-lingual’ child is ‘dominated by a chaotic mix of perceptions, feelings, and needs’, it cannot distinguish itself from its own mother and is, most importantly, ‘closest to the pure materiality of existence, or what Lacan terms “the Real”’.

Once again, I turn to Fisher to complicate these ideas, and specifically to his analysis of the curtain motif that binds all of Lynch’s performative spaces together:

‘Curtains […] both conceal and reveal […] they do not only mark a threshold; they constitute an egress to the outside’

Lynch’s curtains not only mark the divide between what is onstage and what exists in the ‘real’ off-stage world, as heterotopic theory describes, but also points to the presence of what might be ‘backstage’, behind the curtain.

Martin, quoting Heidegger, continues this line of thought by noting that…

‘A boundary […] is not that at which something stops but […] that from which something begins its presenting; [once a boundary appears] unplanned action becomes possible, new modes of being emerge.’

In the same way Lynch used the uncanny doubling and repetition of language in expression to negate the Symbolic Order’s authority, Lynch uses the ‘threat of boundlessness’ that lies beyond his curtained spaces to similarly negate the illusions that reside in the Imaginary Order.

When the bandmaster cries that ‘there is no band’ and yet we hear a band, or when Rebekah Del Rio collapses onstage whilst “singing” ‘Crying’ but the song continues to play, Lynch is creating the uncanny effect described in the previous section.

What makes this effect especially potent in Club Silencio is that whilst Lynch is destabilising the Symbolic, he uses the threat of what lies beyond his curtained spaces to simultaneously demonstrate that spaces of performance, and thus the realm of the Imaginary in its entirety, are constantly undermined by the presence of a boundless, unknowable Real that lurks behind them.

Dismantle & Decompose

By making his characters aware of the fragility of their perceived reality, destabilising the language they use and the performative spaces in which they use it, Lynch ‘dismantles and decomposes reality itself.’

In this ‘pulling apart’, Lynch opens the ‘gap’ or ‘fissure’ that Zizek and Fisher earlier described through which the Real can be momentarily, but powerfully, glimpsed. Lynch creates moments wherein his viewers and his characters are…

‘Confronted with a limit that she/he will experience, but cannot know’.

It follows this logic that the portion of Mulholland Drive that comes after the Club Silencio scene depicts the total decomposition of Diane’s fantasmatic illusions that she has crafted for herself as a defence against the traumatic collapse of her relationship with Camilla.

Betty, who was nothing more than a fantasmatic entity created in the mind of Diane, disappears. Diane’s perceived reality was displayed, decomposed, and she was exposed to the Real that lurked behind it; the delicate balance that the respective structuring devices of the Imaginary and Symbolic Orders – performative illusion and language – collapsed.

Such a collapse is reflected by Lynch in the film’s formal shift after the Club Silencio sequence. McGowan explains that the first part of the film ‘conforms on the whole to the conventions of the typical Hollywood film’.

Citing the classically lit composition of shots, the fluid nature of the dialogue, and the ‘sparkling’ décor, McGowan contrasts these with the ‘darker’ interiors of the second part, the ‘awkward’ conversations and sets that have become ‘drab, lacking the ubiquitous brightness’ of the first half.

A similar shift is noticeable in the editing style too. In a moment shortly after the collapse of the dream, a sequence takes place where Diane is shown speaking, followed by a reverse shot of Camilla. However, after another shot of Diane, the reverse shot then shows Diane again, rather than Camilla.

By disrupting the shot/reverse shot sequence that in the first half of the film would have been used to ‘sustain the spectator’s sense of spatial and temporal orientation’, now shows that the two parts of the film are ‘ontologically distinct’.

The little blue box inside Betty’s purse, that Rita opens shortly after Betty’s disappearance and in the scene directly following Club Silencio, also functions as a symbol for what results from Diane’s exposure to the Real.

The box, once opened, is seen to contain nothing but darkness, an infinite, unknowable void; precisely the kind of ‘boundlessness’ that was threatened by the curtained space…

‘The camera’s entry into the darkness of the box marks the point at which Mulholland Drive shifts worlds’.

When the camera is subsumed by the void within the box, it engenders a total collapse of the fantasy; by following this shot of descent with alternating shots of Diane lying on her bed, with one showing her asleep and the other showing her dead, it becomes clear that ‘there is no Betty’ at all, ‘there is no hope’ as ‘there was no band’.

Knowable reality, built upon language and illusion, is revealed to be utterly ‘fluid’, and Lynch’s viewer is left ‘straining to fit the splinters back together into a whole.’

Silencio

However, despite the depicted collapse of Diane’s fantasy that was predicated upon illusory images of the Imaginary and, primarily, the structuring language of the Symbolic that ‘remakes [fantasy] into a fully developed narrative’, Mulholland Drive’s final scene, wherein a blue-haired woman sits in the Club Silencio balcony and mouths the word ‘silencio’, should not be read as a call to quiet.

Though Lynch does attempt to depict the totalising power of the Symbolic in his films, and to undermine it by gesturing towards the underlying Real with uncanny techniques, it is only by ‘insisting on fantasy to the end’ that Lynch can truly expose the ‘traumatic silence of the Real’.

The noise of language, of the Symbolic, is momentarily silenced, and its boundlessness consumes the subject; only by following the logic of fantastical Symbolic-Imaginary reality to its very endpoint, can Lynch ‘achieve the impossible.’

Bibliography

Primary

Lynch, David, dir., ‘The Alphabet’, created 1968, released on The Short Films of David Lynch, (USA: Scanbox, 2002), [DVD]

Eraserhead, (USA: Libra Films International, 1977), [on DVD: Universal, 2001]

The Elephant Man, (UK: EMI Films, 1980), [on DVD: eOne Film, 2001]

Blue Velvet, (USA: De Laurentiis Entertainment Group, 1986), [on DVD: Prism Leisure, 2004]

Wild at Heart, (USA: The Samuel Goldwyn Company, 1990), [on DVD: Universal, 2005]

Lost Highway, (USA: October Films, 1997), [on DVD: 4front, 2002]

Mulholland Drive, (USA: Universal, 2001), [on DVD: VvI, 2002]

Inland Empire, (USA: 518 Media, 2006), [on DVD: Optimum Home Entertainment, 2007]

Secondary

Althusser, Louis, ‘Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses’, last accessed 14 March 2019, <marxists.org>

Berry, Betsy, ‘In My Dreams: Generic Conventions and The Subversive Imagination in Blue Velvet’, Literature / Film Quarterly, 16.2, (1988), 82-89

Felluga, Dino, ‘Modules on Lacan: On the Structure of the Psyche’, Introductory Guide to Critical Theory, last accessed 14 March 2019, <purdue.edu>

Fisher, Mark, Capitalist Realism, (London: Zero Books, 2009) The Weird and The Eerie, (London: Repeater Books, 2016)

Foucault, Michel, ‘Of Other Spaces’, trans. Jay Miskowiec, Diacritics, 16.1, (1986), 22-27

Hudson, Jennifer A., ‘“No Hay Banda, and yet We Hear a Band”: David Lynch’s Reversal of Coherence in Mulholland Drive’, Journal of Film and Video, 56.1, (2004), 17-24

Joseph, Rachel, ‘“Eat My Fear”: Corpse and Text in the Films and Art of David Lynch’, Word & Image, 31.4, (2015), 490-500

Lacan, Jacques, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book 1: Freud’s Papers on Technique 1953-1954, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. John Forrester, (New York: Norton, 1991)

Le Seminaire, Livre XVII: L’Envers de la Psychanalyse, ed. Jacque-Alain Miller, trans. Todd McGowan, (Paris: Seuil, 1991)

Lee, Grace, ‘David Lynch: The Treachery of Language’, last accessed 14 March 2019, <youtube.com>

Lim, Dennis, ‘David lynch’s Elusive Language’, last accessed 14 March 2019, <newyorker.com>

Lynch, David, Lynch on Lynch, ed. Chris Rodley, (London: Faber and Faber, 2005)

Martin, Richard, The Architecture of David Lynch, (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014)

McCartney, Stella, ‘Curtains Up’, last accessed 14 March 2019, <youtube.com>

McGowan, Todd, ‘Looking for the Gaze: Lacanian Film Theory and Its Vicissitudes’, Cinema Journal, 42.3, (2003), 27-47

The Impossible David Lynch, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007)

Moon, Michael, ‘A Small Boy and Others: Sexual Disorientation in Henry James, Kenneth Anger, and David Lynch’, Comparative American Identities: Race, Sex, and Nationality in the Modern Text, ed. Hortense J Spillers, (New York: Routledge, 1991), 141-156

Pfeil, Fred, ‘Home Fires Burning’, Shades of Noir, ed. Joan Copjec, (London: Verso, 1993), 227-256

Schwall, Hedwig, ‘Lacan, Or an Introduction to The Realms of Unknowing’, Literature and Theology, 11.2, (1997), 125-144

Stanizai, Ehsan Azari, ‘The Uncanny: Between Freud and Lacan’, last accessed 18 March 2019, <nida.edu.au>

Stein, Richard, ‘“No Hay Banda”: It is All an Illusion’, The San Francisco Jung Insititute Library Journal, 23.3, (2004), 77-84

Toles, George, ‘Auditioning Betty in Mulholland Drive’, Film Quarterly, 58.1, (2004), 2-13

Wieczorek, Marek, ‘The Ridiculous, Sublime Art of Slavoj Zizek’, introduction to The Art of the Ridiculous Sublime: On David Lynch’s Lost Highway, (Washington, University of Washington Press, 2000), 2-7

Zizek, Slavoj, The Plague of Fantasies, (London: Verso, 1997)

The Art of the Ridiculous Sublime: On David Lynch’s Lost Highway, (Washington: University of Washington Press, 2000)

How to Read Lacan, (London: Granta Publications, 2006) King James Bible, last accessed 14 March 2019, <biblegateway.com>

[Unsigned Article] ‘Naked Lynch’, Psychology Today, 30.2, (1997), 28-32