It’s the day for it: the first proper OOJ post is here.

My psychoanalytic stomping ground is the jumping-off point.

Followed by a case study of (wilful) misinterpretation concerning Greek tragedy.

A suggestion about what kind of (cursed, black box) art best breeds such misinterpretation.

And why generative, machinic misinterpretation is the only viable kind of criticism in a cultural landscape where Iron Man has become a global hegemon.

Let’s go.

How The Psychos Get You

Here’s how I fell down the psychoanalytic rabbit hole; a fairly typical path for many an English Lit student:

You’re first put on to Freud during secondary/high school in the most basic way; you know nobody really wants to f*ck their mother but it’s leftfield enough to grab you.

Same goes for the first notion of a subconscious — you don’t properly understand it but the idea that there may be a dark-and-sexy world beyond the perceptible hooks you regardless.

You get on to an undergrad program and they explain to you why Freud rocked the intellectual world… by talking nonsense.

In a terribly underhand move, they then put you on to Lacan, explaining how he expanded on Freud’s findings.

Given his explicit focus on semantics, this is hard to resist for anyone with an interest in language as well as (or within) literature.

During your Lacanian explorations, you stumble across Deleuze & Guattari — usually with the help of some cool art-school-adjacent friends — and you realise, once again, you’ve been chasing down… nonsense.

You arrive at Anti-Oedipus and realise how dangerous and damaging psychoanalysis has always been. You now have two options.

First, become a thoroughbred psychoanalytic scholar; you risk never being taken seriously by contemporaries but sleep easy in the knowledge that there will always be enough people in the same position — and enough associated conferences — to make a groovy little career.

Alternatively, you throw the baby out with the bathwater and embark on a quest to find a whole new framework to understand art and the world; everything thus far has been a juvenile waste of time.

Or — the secret third option — you make the galaxy-brained move as wavegods like Mark Fisher, Paul Preciado, and Todd McGowan have done before:

You accept that there’s a hell of a lot wrong with psychoanalysis — it is constructed under and reinforces a set of terrible wider social constructs and ideologies…

But instead of binning it wholesale you turn it on its head, embrace the parts that work and shave off the rest.

Then, you use them: first, to better understand the very ideologies it was born from (capitalism, colonialism, and so on) and then to create something new, subversive, and exciting.

Can you dismantle the master’s house with the master’s tools? Maybe.

The Tomb Of Oedipus

If you’re willing to accept that idea, it follows that not only should it change our approach to the critical frameworks with which we approach works of art but also the works of art themselves that we chose to criticise.

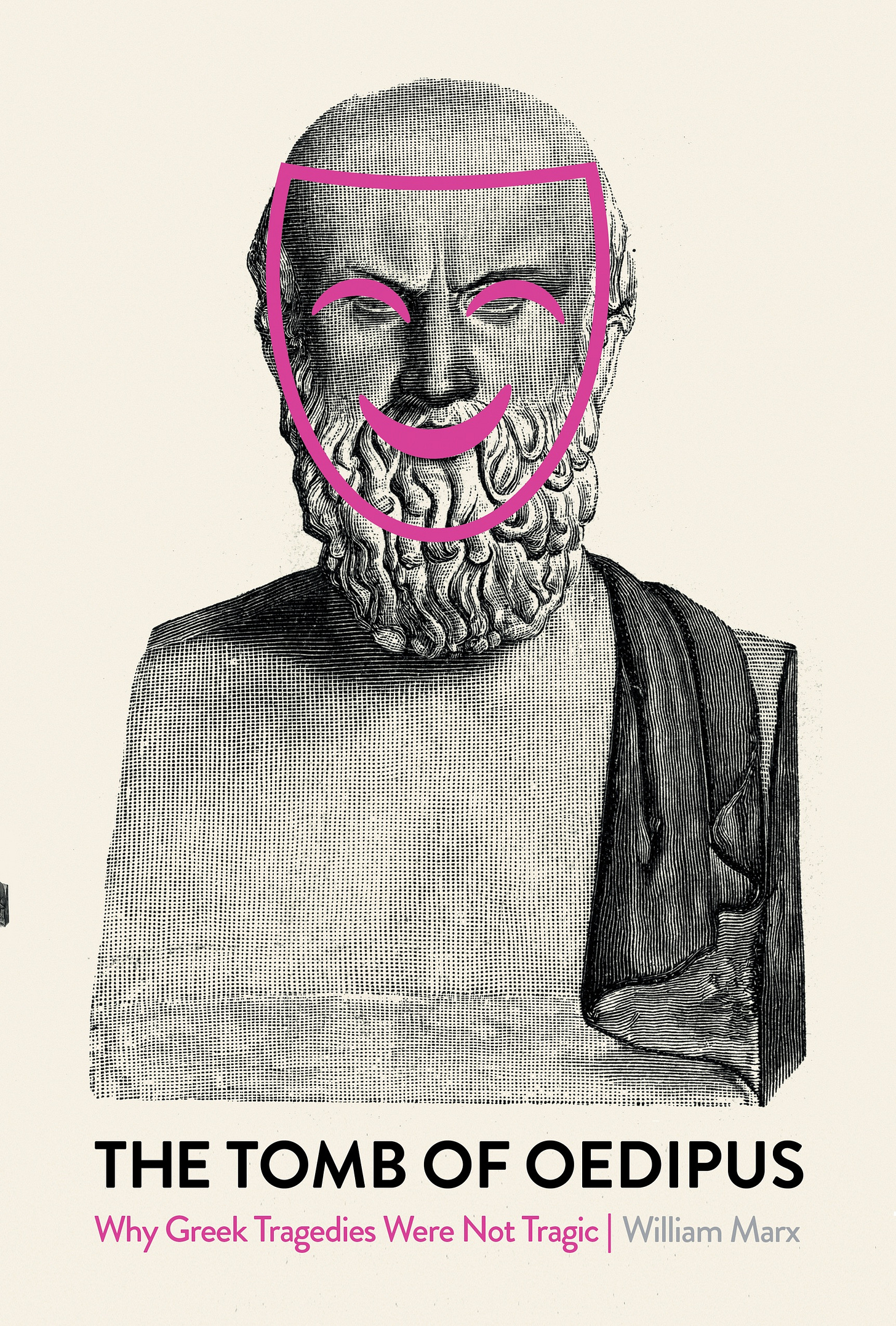

This brings me to the brilliant Tomb Of Oedipus: Why Greek Tragedies Were Not Tragic by (the epically named) William Marx, which I have devoured in recent weeks and cannot recommend highly enough.

At the outset I want to say this: I am no Classical scholar and, frankly, have no ambitions to be. I will be using Marx’s work as a selfish-springboard back to my own areas of interest.

If you have even a passing interest in Greek tragedy, how we understand it, and how it has become so culturally totemic, go and read the book — it is fantastic.

Using Sophocles’ lesser-known Oedipus play — Oedipus at Colonus — Marx’s central contention is summarised perfectly in his subtitle:

Greek tragedies were not tragic and, more specifically, Greek tragedies and what we have come to understand as “the tragic” are not the same thing… at all.

He takes a quote from (the also epically named) Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff to explain what a Greek tragedy really was, bare-bones:

“An Attic tragedy is a self-contained piece of heroic legend, poetically adapted in the sublime style for presentation by a chorus of Attic citizens and two or three actors, and intended for performance as part of the public worship at the shrine of Dionysus.” (p. 58)

Simple enough. The misunderstandings arise in the intervening 2,500 years. Many of the original plays are lost and those that remain go through a complex and compromising set of transcriptions, translations, and alike.

We are left with an incomplete record and so we fall into a trap that Andre Malraux calls “symbols of art”. Using the Winged Victory of Samothrace as his cipher, Marx summarises it thus:

“If we persist in finding it beautiful despite what is missing or […] specifically because of this amputation […] it is with full knowledge of the facts: the reality of this anatomic loss is always present in our mind and can even, if need be, participate in creating the effect of beauty.” (p. 35)

Tragedies feel this effect more acutely than almost any other form.

Even though many of Sophocles’ tragedies “have a looser structure [and] end on a less gloomy note” (p. 68) than his most famous work — Oedipus Rex — the latter has come to define a whole genre.

How? And why? Tragedy became a “victim to concepts”.

This process was started by Aristotle himself when in the Poetics he makes the claim that tragedy “reveals its power by mere reading”; at once decoupling it from performance, place, and body.

The German Romantics take this and run… “the tragic” is born:

“The play is treated solely as a pretext for philosophical discourse. It loses all its substance: the actors drop their masks and robes and leave the stage, soon followed by the chorus and the musicians; the stage wraps itself in clouds; its outlines blur and gradually disappear into space; eventually, instead of a theatre, there is nothing left but a great void, the mere memory of a dream, fit to be filled by concepts.” (p. 53)

Marx points to Hegel, Solger, Hölderlin, Goethe, Schopenhauer, Vischer, and (the still cool-as-hell) Nietzsche as perpetrators of a process that effectively kills Oedipus — “takes [him] away from us, [makes him] totally disappear” only to be “replaced by the triumph of the most abstract and general idea”.

It is an interpretative pivot that echoes all the way down to “Kleist, Yeats […] Artaud, Pasolini, Kieslowski [and even] Star Wars.” (p52)

In short, the physicality of tragedy — its roots in time, place, body — are torn from it outright. Until…

Rare Sigmund Freud ‘W’

In a near-perfect example of the broken clock idiom, one of the very few home runs for Freud is his reconnection of tragedy — and the written word more widely — with the body:

“The fact remains that the only truly consistent link between language and the body to have appeared since Romanticism [was] in the newly created science of psychoanalysis.” (p. 133)

In doing so, he dovetails modern thought with something that Aristotle gets right in the Poetics — catharsis:

“Freud also lays claim to a principle that is, on the contrary, the very foundation of tragic catharsis in Aristotle: the idea, simply, that language, words, or a text can have a direct impact on the functioning of the body; that they can improve a person's well-being, or even effect a cure.” (pp. 134-5)

Freud makes the assertion, which I believe to be absolutely true, that art — written or otherwise — can have a really-existing effect on the psychical world and the bodies therein.

More pointedly: that the interpretation and criticism of said works of art can also have a really-existing effect on the physical world and the bodies therein.

More pointedly still: Freud being right about this proves that even if a critical framework gets loads of stuff wrong or reflects an absolutely twisted set of wider societal assumptions, it can still generate an idea worth holding onto.

Even if the majority of its output is useless, kernels of truth can still be found within:

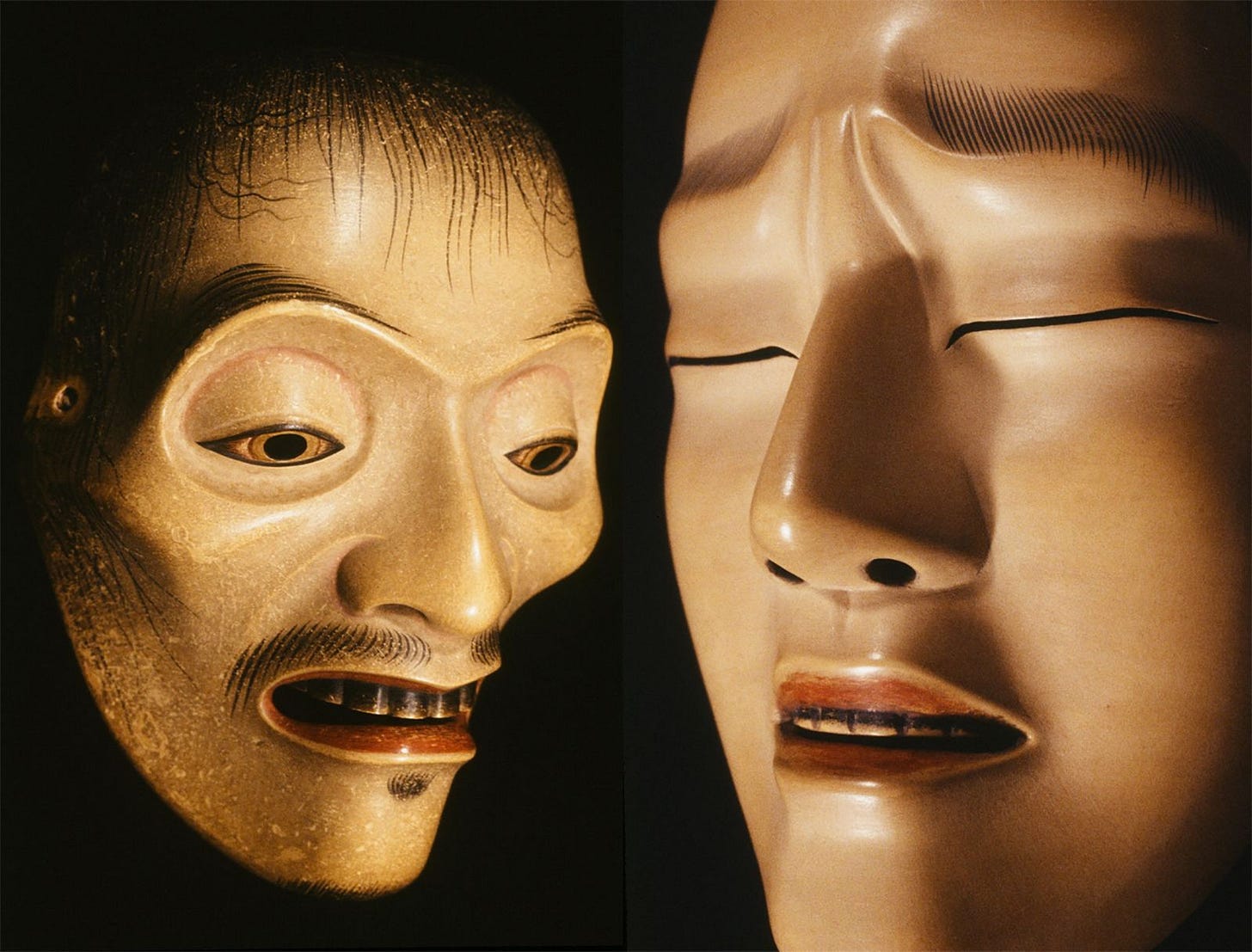

“However great the temptation, we must not search for the truth of tragedy in the tragic, or in what theatre is today — but elsewhere, sometimes very far away: in Noh, psychoanalysis, the Catholic mass. All of these practices and rituals maintain or reproduce, each in its own way, the lost powers of the arts of language.” (p. 191)

Refuse To Elaborate

This begs a question: if we argue that the best criticism functions as an ideas-machine that generates concepts — some useful, many not — which art is best poised to inspire that generation?

Towards the end of the book, Marx proposes a periodisation of the arts that taps into this question precisely.

Marx points out that the best art is, on the experiential level, inevitably impenetrable and inscrutable to some extent:

“We cannot talk about books we have read: we can describe the feelings they arouse, describe them and their settings (historical, cultural, social, and so on), but they themselves remain inaccessible. The work of the highest art is a machine to block definitive interpretation — or to multiply provisional interpretations, which amounts to the same thing. (pp. 193-4, emphasis mine)

Marx’s high-level take is that high-modernism gets this right and high-postmodernism gets this wrong; he offers up (another wavegod) T. S. Eliot as a case study, relaying the following tale:

One day Eliot gets a letter from a pal that says something along the lines of: Any attempt to demonstrate the beauty of art using a rational explanation is a contradiction in terms…

“A rationalistic critic always makes me think of a child breaking his clockwork toy to see what there is inside.” (The Letters of T. S. Eliot)

Eliot listens well and, years later, responds to a question from a student who wants to know what Eliot meant by the famous line from Ash Wednesday: “Lady, three white leopards sat under a juniper-tree”.

The inimitable response:

“I meant: ‘Lady, three white leopards sat under a juniper-tree.’”

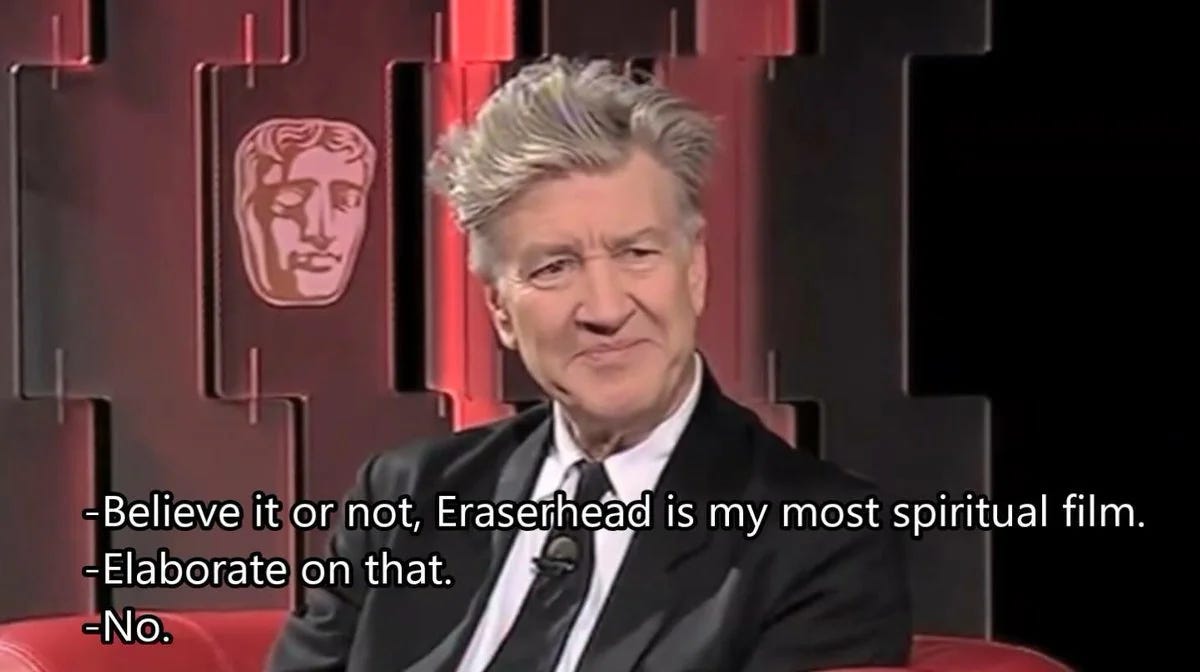

It reminds me of David Lynch’s much-memed refusal to elaborate on Erasherhead being his most spiritual film:

Then compare this shameless obfuscation with contemporary art; not all contemporary art — just the vast majority that makes it into the big-wig, white-walled galleries:

“[Contemporary art] is distinct from modern art in that it refuses the unexplainable. It tends towards pure concept. Once the works have been described, everything about them has been said.” (p. 195)

And, for the sake of archiving, here’s Marx’s periodisation plotted out in three wonderfully concise points:

“First, the work only draws its meaning from the world: a period without art or literature as such;

Then, the work becomes a world itself and opens itself to every interpretation: triumph of art and literature in the strict sense of the term;

Finally, the work vanishes behind interpretation and concept: loss of mystery and the unexplainable.” (p. 196)

Great Art Is A Black Box

At last, we arrive at the point I am trying to make:

The very best art is a black box and the very best artists understand this.

The deliberate obfuscation of “meaning” is an essential component to creating art that generates ideas; that acts in a productive, machinic mode rather than a definitive, foreclosing one.

While I considered extending this critique to the culture-industry at large — not just the artworks themselves but the endless stream of supporting content that the media-machine is obliged to generate in the age of everything-everywhere short-form video….

I think it would be wise to keep my scope a little narrower for now, for fear of needless and unprompted overreaching.

But make no mistake: I will return to that thought in due course.

For now, let’s focus purely on narrative as a vehicle for potential obfuscation… or not.

I’m going to strawman some major movie franchises; I know very few people would point to the MCU as a paragon of avant-garde, boundary-pushing screenwriting…

But given its status as the highest-grossing movie franchise of all time, it occupies a monolithic enough position in our cultural climate to warrant a little kicking.

My main problem when watching these films — or a Star Wars movie, or a John Wick movie, or even a Harry Potter movie (though the latter-day millennial in me feels a twinge of guilt as I type that) — is this:

Whenever I watch these movies, I know who is good, who is bad, and exactly what the ending will be from the outset; the possibility of generative ambiguity is killed stone dead.

At worst, this makes these movies a covert ideological delivery system and, at best, it simply makes them unbearably dull.

The most of the moment point of contrast I can think of is Nathan Fielder’s The Curse.

For transparency, at time of writing, I’ve watched seven of the ten episodes so there’s everything to play for in the home stretch.

What I love about the show is that while it’s crystal clear from the word “go” that all of the three main characters — Whitney, Asher, and Dougie — are “bad” people in the grand scheme of things…

The show remains totally opaque as to who, amongst its main characters, is the “goodie”, the “baddie”, or whatever else; at no point (so far) can I necessarily tell which of them is worse than the other.

This ambiguity vis a vis character is born out of a plotline that itself hinges upon a central ambiguity; is the titular curse “real” or simply imagined into existence through Asher’s bottomless paranoia?

“Are Asher and Whit’s many problems – both of the professional and marital variety – merely the kind of everyday challenges that any working couple face when trying to build something from scratch? Or are they the result of something larger and more cosmic?” (The Globe & Mail)

Which is then echoed at the level of form:

“The Curse makes liberal use of mirror shots and distorted mirror imagery. It pairs these with shots of conversations framed in windows or doorways, or filmed from a great distance, lending the show a voyeuristic quality. What are we truly meant to be seeing?” (Mashable)

Which is then compounded by the unavoidable histories of those involved in crafting said narrative.

As the show tries to make an (ambiguous) point about just how “real” reality TV is, it simultaneously collapses the boundaries between the actual real world and the world of the show, as is Fielder’s longtime modus operandi:

“While the supporting cast is mostly filled out by recognizable faces — including Corbin Bernsen as Whitney’s father, and Captain Phillips scene-stealer Barkhad Abdi as the father of the girl who curses Asher — several of the Espanola locals appear to be, from their mannerisms and halting line deliveries, real-deal community members roped into the show by methods unknown.” (The Globe & Mail)

All of this leads the show to be rightly crowned “the weirdest, most unforgettable show” of 2023.

This self-conscious weirdness, a refusal to be easily understood, leads to much more generative criticism; the most important kind of which is discussion amongst friends.

Having such a discussion about The Curse only yesterday, I was struck by how creative, leftfield, and conflicted everyone involved was about the show, its characters, and their actions; a general “what the f*ck is going on” vibe.

Is this kind of conversation — one that is far-reaching and reproductive — not qualitatively better than simple-minded soyfacing over Tony Stark’s billion-dollar CGI suit or the immeasurable girth of Chris Hemsworth’s newly-juiced biceps?

Here’s a silly little graph to try and sum up what I mean:

Therefore, as critics — for are we all not critics in the always-already networked age of the cloud-based commentariat? — we must not only seek out works that are intentionally inscrutable…

But also embrace our own critical “failure”, wrongness, and irrationality; instead using these artworks to generate off-the-wall, even unhinged ideas, before sharing these with spam-like intensity across the same social networks that legacy media outlets attempt to saturate with their insufferable junkets.

The same written word that is used to oppress you (or simply bore you to death) can, if made strange, eerie, and wilfully weird enough, be the very same language that causes a rupture in the social fabric as it currently exists, that germinates the idea that leads to the world beyond this one.

At least, that’s the theory.

…

New post on cooking & cleaning soon come.